Published: July 2022

Updated: November 2024

How likely is a nuclear war and who would be at risk?

In the context of the ongoing war in Ukraine, the question of a potential nuclear escalation or even a nuclear confrontation has gained renewed relevance and importance.

Contrary to widespread media claims, the Russian government to date has never threatened to use nuclear weapons in Ukraine. In fact, Russia does not currently have a nuclear first-strike policy: Russian nuclear weapons are only to be used in response to a nuclear attack against Russia or in response to a conventional attack that threatens the very existence of the country (e.g. a NATO invasion). The only country with a nuclear first-strike policy currently is the United States. (*)

Nevertheless, one may consider the likelihood and outcome of a potential nuclear war.

A nuclear attack against the mainland of nuclear states remains very unlikely, as this would lead to the destruction of all states involved. However, from a military and geostrategic perspective, there are two rational offensive uses of nuclear weapons, in addition to their defensive use as a deterrent: against hostile non-nuclear states and against overseas military infrastructure of nuclear states.

In this regard, there is a major geostrategic asymmetry between Russia and China on the one hand and the US on the other hand: whereas the US has several hundred overseas military bases and more than two dozen non-nuclear military allies or client states (both in Europe and in Asia), Russia and China have almost no overseas military bases and very few non-nuclear military allies.

Thus, Russia and China could consider coordinated nuclear strikes against all US overseas military bases in Eurasia (i.e. in Europe, the Middle East, Central Asia and East Asia). In addition, Russia and China could consider nuclear strikes against hostile non-nuclear countries, both in Europe and in Asia, targeting military and industrial centers or even population centers.

Theoretically, such a coordinated nuclear attack might effectively remove the US military from the Eurasian continent (and by extension from Africa), limiting direct US military influence to North and South America. Thereafter, a new geo-economic Cold War between Eurasia/Africa, led by China and Russia, and the Americas would likely ensue.

A nuclear attack against non-nuclear NATO states would be seen as an attack against NATO, and a nuclear attack against US overseas military bases would be seen as an attack against the United States, but because of the above-mentioned asymmetry, the US could not respond in a meaningful way without forcing its own destruction. In other words: the US would not sacrifice Boston to save Poznan (in Poland), as a Russian geostrategist recently put it.

Indeed, in Europe the country most at risk of a nuclear strike is likely Poland, and as secret recordings revealed in 2014, the Polish leadership is well aware that just as in WWII, the US and Britain are using their country but would not actually defend it. In Asia, the countries most at risk are likely not Japan and South Korea, but the formerly British outposts of Australia and New Zealand: applying an “Asia for Asians” doctrine, China could terminate both countries and recolonize them.

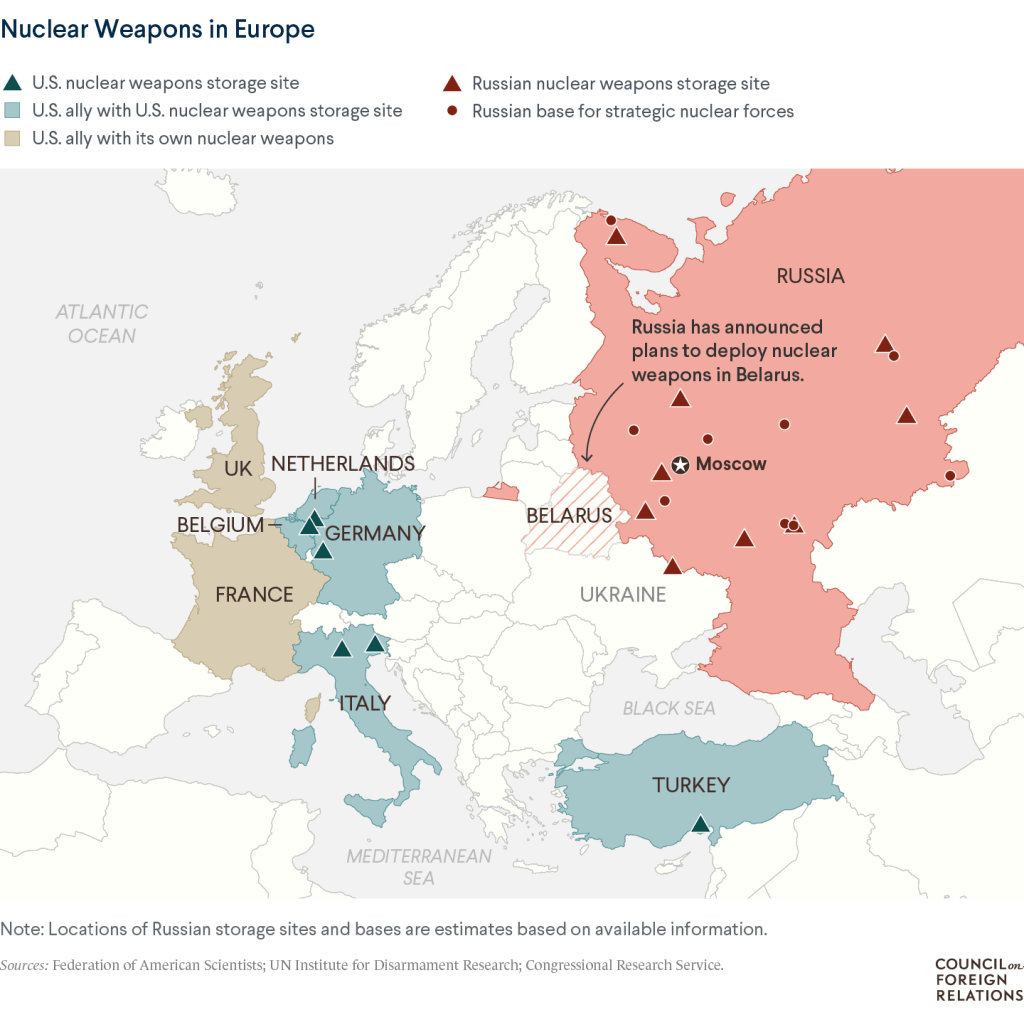

The US does store nuclear bombs in several non-nuclear European NATO countries, most notably in Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Turkey (see map below). But these are relics of the Cold War: in case of a Soviet invasion of Western Europe, the US or its allies could have deployed these nuclear weapons against invading Soviet forces in Western Europe or against non-nuclear Warsaw Pact states in Eastern Europe (i.e. East Germany, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia), but not against the nuclear-armed Soviet Union itself.

Today, the Warsaw Pact no longer exists, and its former members have become NATO members. Thus, the only close Russian ally that NATO nuclear powers may still attack is the former Soviet republic of Belarus. To prevent such a scenario, Russia recently deployed nuclear weapons to Belarus. Another Russian and Chinese ally still exposed to a potential US-led attack is Iran.

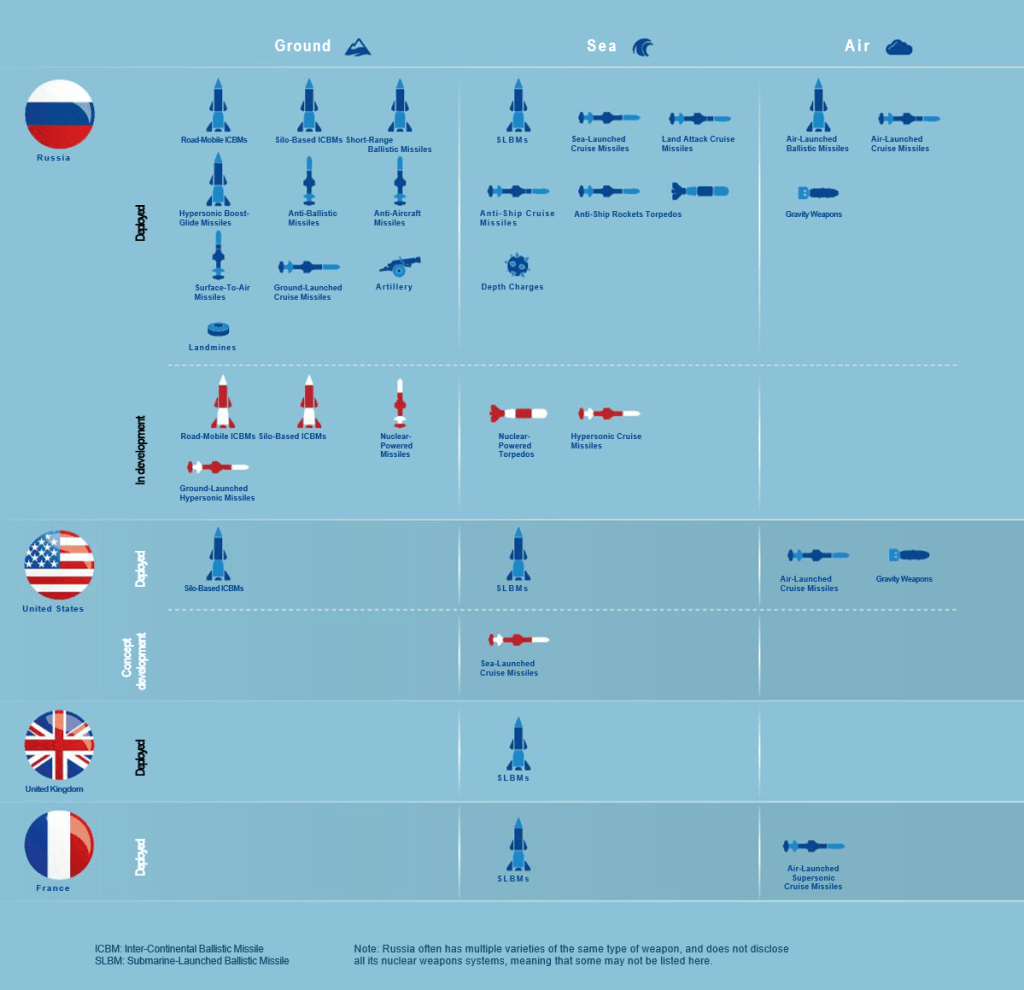

In turn, nuclear allies of the United States in Eurasia, most notably Britain, France, and Israel, have to ensure robust sea- and air-based second-strike capability even against modern hypersonic missiles with multiple nuclear warheads to avoid being targeted themselves. Britain (i.e. England) in particular is known to have a rather limited second-strike capability consisting of just four nuclear-armed submarines, of which only one is normally deployed at a time (see chart below).

While a nuclear war scenario as described above is militarily realistic and even rational (given the breakdown of the post-WWII global security architecture), both China and Russia currently follow a different geopolitical strategy by developing novel alliances such as BRICS, RCEP, the Eurasian Economic Union, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), a security union. In March 2023, even longtime US ally Saudi Arabia announced its decision to join the China-led SCO.

In contrast, the US may still attempt to involve Russia and China in protracted regional conflicts or try to contain them via economic and political sanctions. In both cases, the ultimate goal would be to weaken and possibly overturn their governments, thus paving the way for global US predominance, which was almost achieved after the end of the Cold War.

∗∗∗

Update November 2024: In November 2024, Russia updated its nuclear doctrine. Essentially, the updated doctrine enables Russia to respond with nuclear strikes to any military attack or military threat by a country or a coalition of countries that possesses nuclear weapons. This condition is already met as Ukraine is backed by the US, the UK and France.

As described above, a rational and non-genocidal application of this doctrine would be the simultaneous nuclear destruction of some or all US military facilities in Europe or Eurasia. The United States could not respond to such an attack by counter-attacking the Russian mainland as this would result in the nuclear destruction of the United States itself.

∗∗∗

Nuclear strike simulation

- NukeMap (Wellerstein, 2023)

Map: US and Russian nuclear weapons in Europe

Chart: Nuclear weapons of Russia and NATO countries

Video: Largest Nuclear Tests Caught On Camera

Read more

- The Logic of US Foreign Policy

- The American Empire and Its Media

- Ukraine War: Geopolitical Background