Updated: January 2025

Published: July 2022

Did the United States send men to the moon? The following overview presents the strongest factual arguments and counter-arguments in the moon landing debate.

1) Documentary: American Moon (2017)

American Moon by Italian filmmaker Massimo Mazzucco is the foremost skeptical documentary on the moon landing question. The documentary consists of five parts and raises 42 questions or issues concerning the Apollo moon landings (see screenshots and counter-arguments below).

Video: American Moon by Massimo Mazzucco (210 minutes; website)

2) Counter-arguments to the documentary

The strongest counter-arguments to the 42 points raised in American Moon.

- Debunking “American Moon” (I) (questions 1 to 21, Reddit)

- Debunking “American Moon” (II) (questions 22 to 31, Reddit)

- 42 answers to “American Moon” (Moon and Beyond, translated)

3) Screenshots from “American Moon”

25 pivotal screenshots from the “American Moon” documentary, covering moon landing simulations, Van Allen radiation belts, moon rocks, lunar dust, lunar module quality and lift-off, the missing Apollo tapes, Apollo audio tracks, several photographic aspects, and the astronauts.

4) Lunar gravity and sound analysis

Skeptics argue that lunar gravity was simulated using monofilament wire suspension and variable frame rates (i.e. dynamic slow-motion), but that some scenes reveal Earth gravity. Furthermore, skeptics argue that some scenes reveal sound transmission, despite the lack of a lunar atmosphere.

Skeptics have also argued that in Apollo moon footage, all movements, not just vertical (free fall) movements, appear to be in (variable) slow-motion. In addition, skeptics noted that astronauts in Apollo moon footage were jumping merely knee-high, while astronauts in transverse lunar gravity simulation experiments are able to jump well over one meter high.

A comprehensive frame rate and gravity analysis based on the original Apollo footage was first performed in 2015 in a three-hour video investigation titled “Apollo: Make Believe”. The following short video clips show examples of this analysis reproduced by the Apollo Project. This type of skeptical analysis has not yet been addressed by supporters of the official Apollo version.

- Apollo Lunar Gravity Analysis (AP 2015, 5 min.)

- Apollo Lunar Sound Analysis (AP 2015, 3 min.)

- Apollo Jump Salute Analysis (AP 2015, 2 min.)

- Full video: Apollo: Make Believe (160 minutes)

Image: Apollo frame rate and gravity analysis (AP)

5) Lunar landing simulations

Prior to the Apollo moon missions, NASA performed several highly realistic lunar landing simulations. In a 2003 documentary, Apollo Flight Director Gene Kranz stated that: “The simulations were so real that no controller could discern the difference between the training and the real mission.”

In the same documentary, Kranz stated that one week before the launch of Apollo 11, NASA had to abort the final lunar landing simulation due to computer problems (see video below).

Thus, contrary to common belief, only a few people had direct access to events that occurred beyond low Earth orbit. In a 2002 documentary, even German NASA scientist Ernst Stuhlinger, who together with Wernher von Braun designed the Saturn V rocket, said about his knowledge of the Apollo moon landings: “I watched the television screen and believed what I saw.”

Both Ernst Stuhlinger and Wernher von Braun were transferred from Germany to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip, a post-WWII US military and intelligence operation, and both men collaborated with Walt Disney on three films about moon missions and space exploration.

However, von Braun and Stuhlinger were only responsible for the “visible” part of the Apollo missions, i.e. the launch of the Saturn V rockets on Earth. The “invisible” part – operations beyond low Earth orbit – was managed by Robert R. Gilruth. Gilruth previously was assistant director of NASA’s Pilotless Aircraft Research Division, which developed remote-controlled aircraft.

US government agencies have used simulations and exercises to stage other televised events, including alleged “terrorist attacks” such as the 2013 “Boston Marathon bombing”. Moreover, in the 1990s high-resolution computer analyses revealed that the world-famous “Zapruder film” showing the 1963 JFK assassination was in fact a sophisticated fabrication. Thus, passing off simulated moon landings as real would not constitute a unique or inconceivable accomplishment.

NASA itself has close links to the US military and US intelligence. About two thirds of NASA astronauts have come from military service (including most Apollo astronauts). In 2005, former president of CIA technology firm In-Q-Tel, Michael D. Griffin, became NASA Administrator. In 2019, former NASA Administrator, Christopher Scolese, became director of US space intelligence agency NRO.

Video: Gene Kranz on lunar landing simulations (Failure Is Not An Option, 2003)

6) The Saturn V rocket

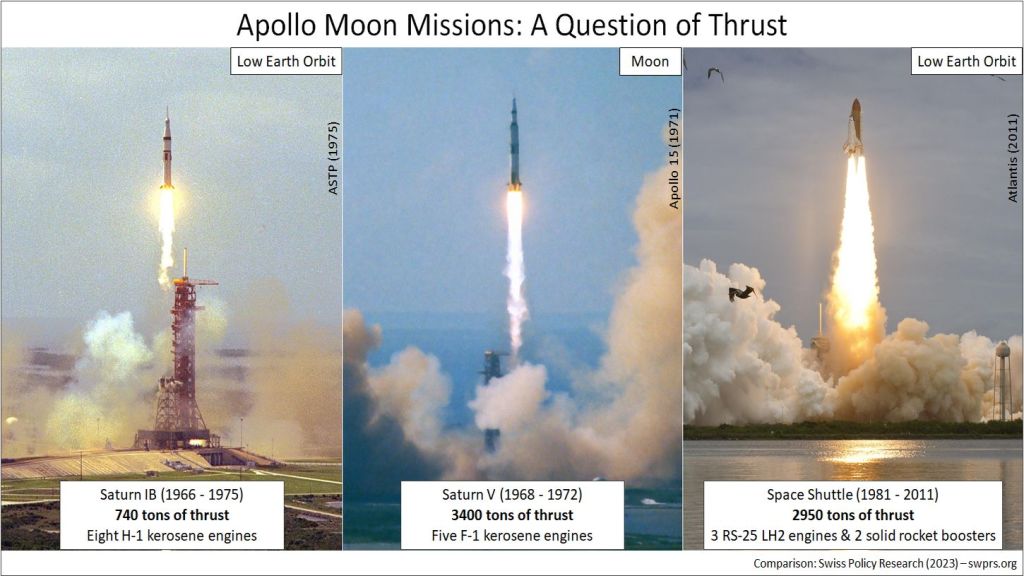

While the moon landing debate has mostly been focused on the actual moon landings, additional questions concern the Saturn V rocket used for the Apollo moon missions (center in figure above).

According to official data, the five F-1 kerosene engines of the Saturn V rocket (1968-1972) produced a combined thrust of 3400 tons at liftoff. This was almost five times more powerful than the Saturn IB rocket (1966-1975), whose eight H-1 kerosene engines produced a combined thrust of only 740 tons at liftoff. Moreover, it was almost 20% more powerful than the total thrust of the Space Shuttle (2950 tons, 1981-2011), which used two solid rocket boosters in addition to the three RS-25 main engines.

However, skeptics have argued that the actual thrust of a Saturn V rocket appears to have been rather similar to the thrust of a Saturn IB rocket and rather lower than the thrust of a Space Shuttle. Furthermore, skeptics have argued that the measurable acceleration of Saturn V rockets during liftoff and ascent was three times lower than required to transcend low Earth orbit (see video comparison below). In addition, skeptics have argued that reported Apollo atmosphere re-entries, allegedly observed by airline pilots, appear to have been staged. In short, skeptics suggest the F-1 engine never reached its stated power and, thus, the Saturn V rocket was unable to reach the moon.

According to official data, the F-1 engine produced almost eight times more thrust than any other American kerosene rocket engine ever built and almost four times more thrust per combustion chamber than the largest Soviet kerosene rocket engine (see chart below). The F-1 engine was beset by instabilities during its development in the 1960s, but apparently worked without a single failure during the Apollo moon missions. Nevertheless, it was scrapped in 1973 and can no longer be built today because “there are simply not enough people with the necessary skills”.

In terms of rocket weight, the reported weight at liftoff was 590 tons for the Saturn IB, 2,900 tons for the Saturn V, and 2,000 tons for the Space Shuttle, resulting in an official thrust-to-weight ratio at liftoff of 1.25 for the Saturn IB, 1.2 for the Saturn V, and 1.5 for the Space Shuttle.

The SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket, first used in 2018, achieves a thrust of 2,300 tons at liftoff (i.e. 30% less than the Saturn V). The SpaceX Starship Super Heavy booster, first tested in 2023, achieves a maximum thrust of 7,600 tons (i.e. 120% more than the Saturn V). However, the Starship Super Heavy uses 33 liquid oxygen (not kerosene) Raptor 2 engines; thus, the maximum thrust per engine (230 tons) is three times lower compared to the five F-1 engines used by the Saturn V rocket.

Figure: The Saturn V F-1 engine compared to other US and Russian kerosene rocket engines (MF)

Video: NASA Rockets: Launch Comparison (SPR, 2023)

7) Other NASA achievements

Prior to the manned Apollo moon missions, NASA launched several unmanned lunar missions that were designed to achieve hard landings, soft landings, lunar orbits, and lunar liftoffs.

However, prior to the manned Apollo 11 mission in July 1969, NASA had achieved only one unmanned lunar liftoff of just four meters (by the Surveyor 6 mission in November 1967) and no complete lunar liftoff and return to Earth. Moreover, prior to the manned Apollo 8 lunar orbiting mission in December 1968, NASA had not sent any animals through the Van Allen radiation belts.

The first lunar mission to include animals (two tortoises), traverse the Van Allen radiation belts, circle the moon and return to Earth was the Soviet Zond 5 mission in September 1968. The first unmanned spacecraft to successfully lift off from the lunar surface and return to Earth was the Soviet Luna 16 mission in September 1970. Even so, the USSR never sent men beyond low Earth orbit.

In 2004, US President George W. Bush announced a program to achieve a “return to the moon”, but twenty years later, NASA had only completed a single uncrewed moon orbiting mission. Moreover, the current NASA Artemis program will require at least 15 rocket launches for orbital refueling and space transfer to execute a single manned moon landing attempt.

Between 2019 and 2024, ten unmanned missions from six countries (the US, Japan, China, India, Israel, and Russia) tried to reach the lunar surface. Two of them failed to reach the moon, four crash-landed, two landed sideways, and two (from China and India) landed successfully.

In 2024, on its first crewed test flight, the Boeing Starliner brought two astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS) in low Earth orbit but could not bring them back due to thruster failures and helium leaks. Development of the Starliner spacecraft began in 2010, cost over $5 billion, and should have been completed in 2017.

In a 2016 interview, veteran NASA astronaut Don Pettit made the following statement: “I’d go to the moon in a nanosecond. The problem is we don’t have the technology to do that anymore. We used to but we destroyed that technology and it’s a painful process to build it back again.”

Apollo skeptics suspect that humans cannot travel safely through the Van Allen radiation belts. According to official reports, there were four space missions that carried higher animals through these radiation zones: three Soviet Zond missions in 1968/1969 (carrying several turtles) and the American Apollo 17 mission in 1972 (carrying five mice). In 2024, for the first time since the Apollo missions, the SpaceX Polaris Dawn mission carried four humans to the lower edge of the inner Van Allen belt at an altitude of 1,400 km, three times higher than the International Space Station (ISS).

Figure: The Earthrise photograph reportedly taken during the Apollo 8 mission in 1968 (NASA)

8) Photographs of Apollo lunar landing sites

To date, no high-definition photographs of the Apollo lunar landing sites have become publicly available and no robotic lunar mission of any country has ever visited the Apollo landing sites. However, several lunar orbiters have provided low-resolution images of Apollo landing sites.

In 2012, when private robotic moon missions participating in the Google Lunar X-Prize announced their intention to visit Apollo landing sites, NASA imposed no-fly zones and ground-travel buffer zones to “protect and preserve the historic and scientific value of US government lunar artifacts”.

In December 2020, US Congress passed a law that declared all six Apollo lunar landing sites national heritage sites and off-limits to any other nation or private space company.

In 2002, European astronomers announced they would use the newly built Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile to achieve “a high-resolution image of one of the Apollo landing sites” and “kill off the conspiracy theory once and for all”. However, a single mirror of the telescope achieved a maximum resolution of only 130 meters, while images using all four mirrors of the telescope, expected to be “sufficiently sharp to show something at the sites”, were never taken or never published.

In 2009, NASA released low-resolution photographs of Apollo landing sites taken by NASA’s own Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO, see below). Skeptics disputed the authenticity of these images and argued that the LRO camera should have been able to provide more detailed photographs.

In 2012, a Chinese official stated that Chinese scientists “spotted traces of the previous Apollo mission” in images taken by the Chang’e 2 lunar probe, but the resolution of the publicly released Chinese moon maps was not sufficient to identify any landing sites. Subsequent Chinese moon missions apparently didn’t take photographs of the Apollo landing sites.

In 2021, during a Youtube webinar, an official of the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) unveiled two low-resolution photographs of the Apollo 11 and 12 landing sites reportedly taken by the Indian Chandrayaan-2 lunar exploration mission. These are currently the most detailed landing site photographs available, but skeptics have disputed their authenticity and origin.

The Japanese Kaguya probe in 2008 and the South Korean Danuri probe in 2023 also photographed Apollo landing sites. The quality of their images is lower than that of the American and Indian images, but they appear to be consistent with one another. Moreover, Kaguya provided a 3D lunar terrain reconstruction consistent with Apollo 15 surface photographs (see below).

If the Apollo lunar landings were faked, faking a few low-resolution landing site photographs 50 years later would be comparatively easy but would likely require international cooperation. In contrast, if the landing site photographs are genuine, the Apollo lunar landings were probably genuine, too.

It is sometimes argued that lunar laser ranging experiments prove that NASA astronauts placed so-called retroreflectors onto the surface of the moon, but this claim doesn’t hold up.

First, lunar laser ranging experiments were performed already before the Apollo missions; second, a 2020 study published in the American Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics found that there is no evidence the alleged NASA retroreflectors improved lunar laser ranging; and third, two unmanned Soviet moon missions (Luna 17 and 21) also placed retroreflectors onto the moon.

Some amateur astronomers claimed they were able to monitor Apollo moon landings with home-made radio telescopes that picked up the astronauts’ voice messages. While this is difficult to verify, it wouldn’t be proof of manned moon missions, either: already in 1968, the Soviets tricked the Americans into believing they landed on the moon by equipping the unmanned Zond 5 mission with a radio transmitter that played voice messages sent from the command center on Earth.

Read more: Third-party evidence for Apollo Moon landings (Wikipedia)

Figures: Photographs of Apollo landing sites (slideshow)

Image sources: PetaPixel / NASA / Wikipedia / ISRO / JAXA / KARI

9) Russian and Chinese skeptics

Several Russian scientists and engineers, including veterans of the Soviet space program, have questioned the Apollo moon missions. The highest-ranking Russian official to publicly doubt the American moon landings is Dmitry Rogozin, former chief of Russian space agency Roscosmos.

In a 2023 interview (shown below), Rogozin raised questions concerning both the available technology and the astronauts themselves. In addition, Rogozin argued that there is still no independent verification of the American moon landings (see discussion above).

Prior to the Apollo missions, some American scientists and engineers suspected that the Soviets faked their own manned space missions, including the first “spacewalk” and the first manned orbital space flight, as documented in a 1966 issue of Science and Mechanics titled “Russia’s Space Hoax”.

In addition to Russian scientists, some Chinese space scientists have also voiced skepticism about the reality of NASA’s manned moon missions. China’s own robotic lunar exploration program, known as the Chang’e Project, completed its first lunar mission in 2007.

A 2016 survey found that 52% of British citizens didn’t believe NASA’s manned moon landings of the 1960s and 1970s were real, including 73% of young British adults aged 25 to 34.

One of the first groups to publicly question the manned Apollo moon landings was the so-called “Flat Earth Society”. The group was founded in 1956, at the very beginning of the Space Race, by British lecturer Samuel Shenton, a fellow of both the Royal Astronomical and Royal Geographical Societies. The group is widely seen as a prank or psyop distracting from serious investigations.

On the other hand, in 2024 SpaceX CEO Elon Musk stated in an interview that “We definitely went to the Moon. I swear. We went to the Moon several times.”, while Roscosmos chief Yuri Borisov stated that lunar soil samples proved the US moon landings were real. Skeptics of course noted that Musk was a major US military and intelligence contractor, while lunar soil samples had been collected by robotic missions and even by Antarctic expeditions, including by NASA’s von Braun in 1967.

Figure: Former Roscomos chief Dmitry Rogozin on NASA moon landings (2023)

10) Additional articles and videos

Additional information on technical, historical and political aspects.

Videos

- The Moon Landing Debate (SPR Media Archive)

Apollo skeptics

- China: Was Whitey on the Moon? (Godfree Roberts, 2024)

- Were Apollo Atmosphere Re-Entries Faked? (Popov, 2013)

- Did the USA Really Go to the Moon? (Serendipity, 2013)

- Wagging the Moondoggie (David McGowan, 2009)

- Saturn V Launch Analysis (Popov/Bulatov, 2013)

Counterarguments

- “Moon Hoax” – Debunked (Paolo Ativissimo, 2020)

- Debunking “Wagging the Moondoggie” (SS, 2020)

- Third-party evidence for Apollo Moon landings (WP)

- Moon landing conspiracy theories (Wikipedia)

Reader feedback

- “An unusually good article that summarizes a large part of the arguments for the Apollo 11 moon landing being a fake, as well as the counterarguments. Unlike most other things that can be found, it is factual and concise, and you get a pretty good overview of the debate. Incidentally, I can also mention that the article is very good at linking to sources, something that we are not spoiled with when it comes to this debate.” (Flashback, 2024)